Fracture in the family

Sun,Jan 10, 2016 at 08:15PM by Carla Mullins

Pelvic fractures and strategies for dealing with trauma injuries

Reflection on the past year is always interesting. Now and again we gain insight into what we should be grateful for and what we have learnt. As I thought about 2015 I realised there was one standout moment that changed things for our family: when my partner Michael‘s front mountain bike wheel got jammed between two timber planks while riding across a small country bridge near Bellingen in northern NSW. That moment resulted in him being pitched over the edge of the old wooden bridge, landing two metres down below in a very shallow and extremely rocky creek bed.

The fall and the fractures

Michael had hit the rocks hard and realised immediately that he was badly hurt – and cold! It was late afternoon in the middle of winter and the sun had already gone down behind the nearby hills. However he’d been riding by himself and it was a sparsely populated area, plus his mobile phone was broken by the impact of the fall, so help was hard to find. From where he landed in the creek bed he couldn’t easily be seen from the dirt road that led to the bridge, so after unsuccessfully trying to get his phone working, Michael slowly crawled out of the shallow creek bed dragging one leg behind. Once he’d made it to dry rocks he tried to stand up and tentatively walk, but as soon as he put weight on his right leg the instant sharp pain and crunching of bone upon bone convinced him that something was broken in his hip joint or pelvis. So Michael continued gingerly crawling out of the creek bed, up the one-metre high creek embankment and along a small dirt track that ran alongside the creek towards the road. Wet, cold, shivering badly and in some degree of pain and shock, around an hour after the initial fall Michael was eventually able to flag down one of only two cars that had ventured down the dirt road leading to the bridge.

The passer-by who had stopped to assist rang me from his mobile and broke the news, so I quickly drove down to the bridge and we helped Michael into the car. Our five-year old son Max and I then drove him in the dark to the emergency department of a small country hospital about 20 minutes away. Later that night he was transferred by ambulance to a larger regional hospital, where x-ray and CT scans confirmed that he had multiple fractures to his right pelvis: avulsion fracture to the ischial tuberosity; fractured pubic rami inferior and pubic rami superior; complex fracture to the sacral ala; horizontal fracture of S1 lamina. The orthopaedic surgeon commented that he typically saw those types and extent of fractures in car accident patients after sudden high impacts. Fortunately for Michael there was no internal bleeding, organ damage or injury to his spine.

The rehabilitation

That incident meant that my years of assisting other people and their families with injury and rehabilitation were going to benefit our own family. In summary these are the areas that helped with a successful rehabilitation:

// Being part of a broad community.

// Resilience.

// Understanding what the specialists and medical practitioners were saying (and not saying) and insisting on getting answers with the best possible treatment.

// Understanding of fracture healing and how to adapt the pilates method to individual situations.

// Personal discipline of the clients and teaching them to work within their limits.

// Supportive workplace studio environment.

// Some fabulous pilates work (and the second part of this article goes through some of the rehabilitation process and the approach).

I also learnt plenty on how to work with fractures and pelvic rehabilitation in a pilates studio. I also learnt that working with your partner/husband/wife could have certain challenges, particularly when it comes to “listening to and hearing instructions”!

The community

We live in Brisbane and Michael’s accident happened about five hours drive from home in northern NSW. This meant that he was in hospital away from home for a month and could not be moved back to Brisbane. Managing his health needs, three studios and a five-year old child was challenging to say the least! Fortunately the friends I had made in the pilates community stepped up to help. I am particularly thankful to Suzanne at Hara Beyond Movement Studio who opened her home to me, visited Michael when I had to return to Brisbane and showed amazing kindness and practical help. It highlighted to me that there is an amazing community of people who teach pilates and I am thankful for being part of that community.

We also had our community of friends, with some good friends driving down and staying with us that first week. They helped look after our son Max whilst I ran back and forward from hospital. Other friends and family members helped in just the everyday practical things once we returned to Brisbane.

Resilience

The ability to cope with adversity and change is hard. We all have moments when we want to sit in the corner and just rock when things are bad, but we can’t stay in that corner. I was fortunate enough that the whole family including, including Max, managed to get out of the corner and sort things. I admit that I may have taken up eating as a hobby to help me through the process, probably not the best strategy, but I did get out there and commute between Brisbane and the hospital for a month and Michael did do his exercises and rehabilitation at every possible opportunity. The ability to focus and get through things has meant that in just under six months Michael was able to get back on his surfboard and go surfing, plus I have been able to give up the hobby of eating and return to a more healthy strategy of pilates and moderation.

Resilience is essential for surviving the adversities that life throws at us, both in our professional and personal lives. How we develop that resilience and maintain it in a busy life through intelligent daily practice is just as important as physical activity.

Asking questions and insisting on sensible answers – making sure rehabilitation starts on day one

When we took our first step into “hospital world” it soon became obvious that you cannot always just accept at face value what you are told. The orthopaedic specialist had given Michael verbal advice as to the nature and extent of his fractures, however the hospital wouldn’t provide us with a copy of the CT scan and x-ray results. After repeated requests and a few incidents we were finally given the scans and reports to review. It was only then we discovered that there were more fractures involved than we were first told. The reports had not been thoroughly reviewed by the orthopaedic specialist and he’d missed one of the fractures (S1 lamina), even though it was clearly stated on the radiologist’s report. The meant that weight bearing was not appropriate at that early stage (i.e. within 3-4 days of the accident). So unfortunately there were about four days of inappropriate weight bearing exercises before the information was provided, but in the meantime these exercises had caused some nerve damage. This setback delayed Michael’s recovery by at least a week.

There were a number of incidents similar to this and it meant a fair bit of energy was spent being pushy about getting the right information and ensuring that the most appropriate treatment plan was applied. Don’t get me wrong I appreciate that the doctors, nurses and physiotherapy staff were doing the best they could but their focus was on emergency care, and not necessarily on the longer-term rehabilitation objectives. Our focus was on ensuring rehabilitation started from day one, and that meant exercises for Michael in his bed, finding ways to use the hospital bed to help maintain Range of Movement in the spine, arms and good leg, none of which seemed to be a focus elsewhere in the busy hospital environment. I was bringing him balls and bands to help maintain movement and he was keen to do as much as possible.

One of the hard things for Michael was accepting the limitations and respecting the healing process. Whilst I encouraged him to do as much as possible, it was hard for him to accept that “what was possible” was a lot less than in his previous experiences. At first just trying to go to the toilet or shower was a painful and exhausting ordeal and would take him hours to recover. We had to work on his expectations as to what was possible and how to actually wait for things to heal.

The process and some tips on how to deal with pelvic fractures

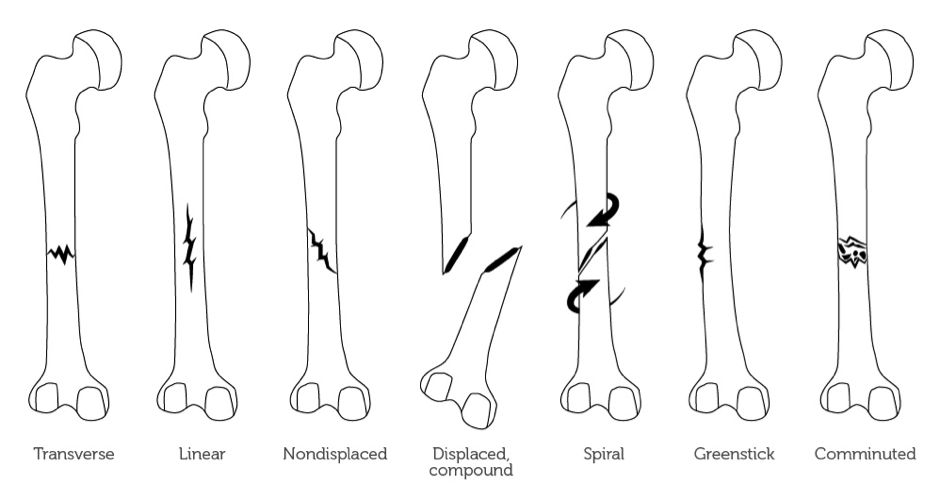

When it comes to fractures of any bones it is always important to know the type of fracture with which you are dealing. Below are basic definitions of the different fracture types:

// Transverse: The bone is broken in two, with the fragments remaining in place.

// Spiral: The line of force is at an oblique or a rotational force line that has been applied, resulting in the fracture.

// Comminuted: There is more than one fragment of bone, which can also be referred to as a segmental fracture.

// Greenstick: The bone is buckled or bent.

// Compression: The cancellous bone is crumpled.

// Avulsion: Where a fragment of bone has been torn away from the main bone by a ligament or tendon.

When dealing with fractures it is important to know whether or not the fracture is displaced or non- displaced. In other words, has the bone moved significantly apart and therefore needs to be pinned back together? It is also important to understand whether the bone is at risk of becoming displaced if there is any weight bearing, which is particularly relevant to pelvic and lower limb fractures. In Michael’s case weight bearing too early resulted in a slight displacement of the sacrum, resulting in pressure on nerves of the sacrum and a great deal of pain. This weight bearing occurred because that fracture was not correctly identified.

Fracture healing

Healing of bone occurs in five stages:

1. Tissue death and haematoma formation: Vessels are torn and a haematoma forms around and within the fracture. Bone tissue dies, 1-2mm of cellular death on either side of the fracture (48 hours from fracture).

2. Inflammation and cellular proliferation: Acute inflammatory reaction under the periosteum and within the breached medullary canal. Fracture ends are surrounded by cellular tissue, forming bridges and allowing for capillary growth (first 1-2 weeks).

3. Callus formation: The proliferating cells are chondrogenic and osteogenic. Under the right conditions, bone with cartilage forms. Osteoclasts commence mopping up dead bone. The immature group of cells forms a callus/splint on the periosteal and endosteal surfaces (2-3 weeks).

4. Consolidation: With continuing osteoclast and osteoblastic activity, the woven bone is transformed into lamellar bone. The system is now rigid enough to bear normal loads (6-12 week stage).

5. Remodelling: The fracture has been bridged by a cuff of solid bone, which will form over a period of months. Following formation of solid bone, which may take years, there will be continued reformation/absorption of bone and adaptation in order to reinforce areas of high load (12 months plus).

The periods of time mentioned above for bone healing is indicative only and can vary depending on a person’s health, diet and age.

What this means when dealing with pelvic fractures is that in more severe cases (and where there has been no surgical intervention) the healing process will result in limited weight bearing for at least 6-8 weeks, with the following implications:

// Hydrotherapy will be important, as it will allow movement without the impacts of gravity.

// Trauma related osteopenia and therefore implications of bone fragility, that is bone weakening in other parts of the body as the body focuses on healing the trauma area. Care needs to be taken so they don’t fall and cause other fractures or overdo things too early and cause stress fractures, for example in the feet (which happened in Michael’s case).

// Pain killers will assist the person through the healing process, but could result in balance and dizziness issues, so care that they do not fall and make things worse. And of course the potential risk of addiction to painkilling drugs needs to be managed.

// An appropriate diet is important, so make sure there is a good dietitian or nutritionist to help ensure the correct balance of supplements to help with bone, muscle and nerve damage.

// Caution with muscle strength and activation, particularly if there has been an avulsion fracture. The last thing you want to create is even more muscular pull on the bone and cause it to be further fractured.

// Peripheral sensitivity.

// Muscular strength and loss on the affected side.

// Muscular tightness from over use in the non-affected side as well as in the hands and shoulder from using crutches and support frames.

Introduction of weight bearing

Having not weight borne on his right side for nearly eight weeks, there were some issues that Michael did have when he eventually did start to work on both legs. His first problem was that his foot had acquired peripheral sensitivity, as it had lost a lot of its sensory memory from having no pressure on the foot. The result was a lot of pins and needle type pain as he was walking around, and very little tolerance for pressure on his feet for a few weeks. Our physiotherapist had advised Michael of the important of sensitivity work throughout the process and had given him some exercises to help mitigate the pain.

What is peripheral sensitivity?

In simple terms our body receives sensation and feedback through our skin and that creates a feedback loop in our brain. When we don’t use a part of our body for a while the feedback loop becomes dulled and we start to get mixed messages from our sensory input system. Something that is normally just an easy movement can start to feel extremely painful – this is the central pain sensitivity we hear about. It is for this reason that it is important that people expose their receptors to sensory input when the body parts aren’t being used because of trauma or damage. In Michael’s case his non-weight bearing feet were exposed to different sensations, e.g. fabrics, textures so that he could keep the sensory pathways working. Scrunching a towel with his foot was also advised. In some people this sensitivity can escalate into quite chronic pain problems.

I had been particularly aware of this issue when Max (my then four year old son) had fallen off some monkey bars and broken his arm (yes, a very accident prone family!). Not surprisingly Max did not take well to following the surgeon’s advice of just keeping his arm in a sling and not moving it for 6-8 weeks. So I took him to an occupational therapist and had a special removable cast made for the elbow, then he could still use his hands and the skin around his affected area could feel water and other sensations. The result being that he was still able to use his hands and did not end up with any sensory issues, particularly as this injury occurred before he was six years old and therefore at a point when important sensory planning and memory systems were being laid down in his brain.

What does peripheral sensitivity mean for your clients?

If you have clients wearing a moon boot or a cast, e.g. because of a foot fracture, then it is important that you work with a physiotherapist or occupational therapist, if possible, to get ideas on how to incorporate sensitisation strategies in the studio setting. Here are some simple ideas:

// Use different textured fabrics and rub them or slide them across the affected area.

// Try marbles, sand, pebbles, theraputty or play dough to help keep the sensory path ways functioning.

// Vary the water temperature to have the person feel cold water, lukewarm water etc.

// In the studio setting you could have the person, for example, resting their feet on different fabrics throughout the class.

Using crutches

When a person has to use crutches to move around they will attest to a number of problems, including:

// Sore wrists and forearms.

// Shoulder pain.

// Tightness and soreness in the weight bearing limb.

When you know someone is going to be using crutches (e.g. upcoming surgery) then it is important to address the hand-wrist strength in advance with specific strengthening exercises. In the case of unexpected accidents, well you just have to deal with the consequences and add it to a long list of things you have to address. I have developed a lovely list of exercises for the upper limbs to help with crutches. Some of these I teach in an upper limbs course, many of which I have learnt from pilates and Gyrotonic teachers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and yoga mudras.

Fractures in a studio setting

Once Michael was able to weight bear, and therefore come out of the hydrotherapy pool, we started to work in a pilates studio setting. When working with a fracture particularly, the considerations are:

// Identify the joints closest to the fracture point, as these are the joints where Range of Motion would have been limited during the first stages of the healing process. Focus on improving Range of Motion in these joints with gravity-minimised loading, e.g. using straps and springs to support the joint as it starts in limited ranges of motion, mainly flexion.

// Identify the muscles that were attached to the affected bone, as these muscles would have atrophied from lack of use during non-weight bearing stages and introduce isometric loaded work for that muscle group.

// Sensitisation work (as discussed earlier in this article).

// As this was a pelvic fracture, once he was allowed to use crutches the weight bearing side was overworked and the supporting muscle groups were tight and overused. Therefore some active stretches were needed, particularly on the piriformis and hip extensors. Eccentrically working on the uninjured side was important but was introduced a little later when both sides were able to cope with eccentric muscular activation.

// Correcting gait pattern and encouraging good lower limb patterning. This meant that a lot of the sessions were done standing and the work was done bilaterally, eventually unilaterally working towards incorporating a lot of uneven surfaces.

// Short sessions for the first month, half an hour three to four times a week. Build the endurance level up to one-hour sessions twice a week, with homework (particularly for feet and ankles). We had special homework sheets for Michael to do at home using bands, balls and towels in order to strengthen the intrinsic muscles of the feet and encourage ROM in the ankles.

To learn more about pelvic fractures and managing them you can undertake our online course Anatomy Dimensions Hip and Femur.

Carla Mullins is co-director and co-owner of Body Organics, a multidisciplinary health and body movement practice with 2 studios in Brisbane. Carla is a Level 4 Professional Practitioner with the APMA and has also studied pilates with PITC as well as Polestar. She also has a LLB (QUT), M. Soc Sc & Policy (UNSW), Diploma Pilates Professional Practice (PITC), Gyrotonic Level 1, CoreAlign Level 1, 2 and 3 and Certificate IV in Training and Assessment.

Michael Schwarer is co-director and co-owner of Body Organics and brings to Body Organics more than 30 years experience working with large Australian and international corporations. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce as well as Master of Business Administration. Injuries sustained in Michael’s weekend warrior sporting pursuits of surfing, cycling and swimming often result in him becoming an unintended rehabilitation case study for the Body Organics team!

0

0