A joint action on Rheumatoid Arthritis with Pilates

Wed,Mar 27, 2019 at 02:41PM by Carla Mullins

I have a distinct memory of a girl in my grade 4 class having Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and how this impacted her. At the time I did not appreciate the pain and the fear that she was experiencing – but I did understand what it was like to be different, and so we became friends. As an adult I have observed family members and clients experiencing Rheumatoid Arthritis, and I still can barely appreciate their pain and frustration. However, I believe I now have the empathy and the skills to help.

This article is written to better inform people of the condition, and to highlight how a well trained and informed Pilates teacher can provide help in a movement class. To learn more about this topic you can register with body organics education for their online courses.

In this article we will be exploring Rheumatoid Arthritis, in particular:

// What Rheumatoid Arthritis is (RA)

// How Rheumatoid Arthritis is different to Osteoarthritis

// How RA is diagnosed

// A review of relevant anatomy and physiology, and how that relates to RA and its symptoms

// Symptoms of RA – including fatigue and pain management

// Medications and their side effects

// Some appropriate exercise choices – with considerations and modifications

Rheumatoid Arthritis is a topic that we explore in our work with clients at Body Organics, and in our Anatomy Dimensions Courses around Australia and the world.

What is Rheumatoid Arthritis?

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is an auto-immune inflammatory disorder that typically affects the joints of the hands, feet and spine. However, it can also affect the neck, jaw and even the sterno-clavicular joint. Whilst it may occur in one joint area, it may not affect other joints. The joints affected can sometimes, therefore, appear quite random. The inflammation can also manifest in the organs and the eyes.

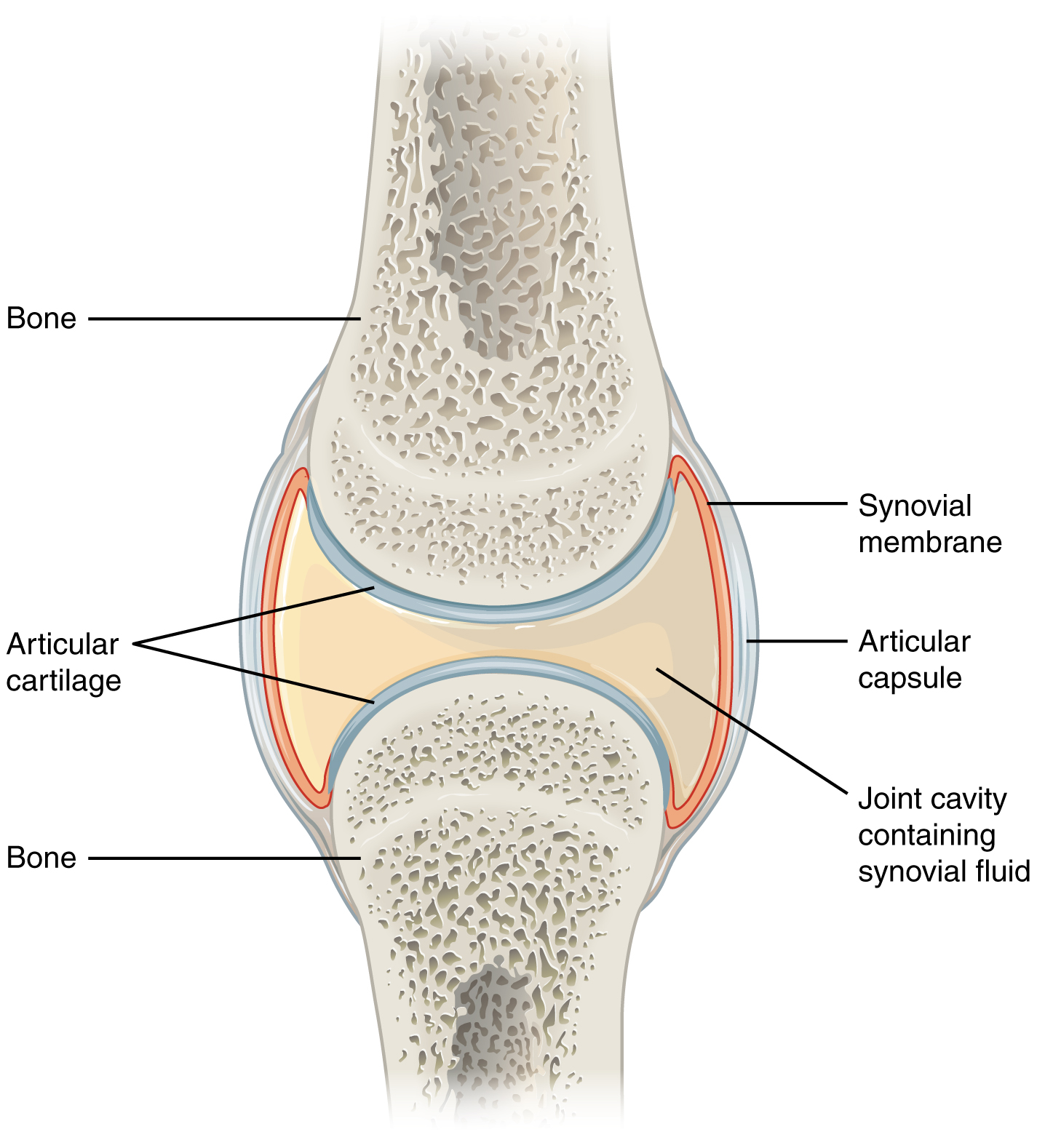

The chronic inflammation that is a consequence of the condition contributes to joint swelling, stiffness, and pain in the synovial membrane of the joint capsule. The synovial lining essentially creates the fluid that helps the joints to slide on each other – it is like the oil that is used in machines to stop friction. When this fluid is reduced, friction can damage the bones from the outside of the bone inwards, due to constant wear and tear. This is important as there are important pain receptors in the outer layer of the bone, and it is part of the pain experienced by those affected by RA. In the later stages, fibrosis (hardening of the soft tissue like scarring) of the joint capsule occurs. Cysts and bone spurs can also form around the joint, contributing to pain and stiffness. All of this can affect the bone and cartilage, thus impacting the movement quality the joint can achieve.

There are genetic predispositions to RA and it can run in families, you must have the gene in order for development. However as with many autoimmune conditions, you are more likely to have RA if you are female. RA has been noted to develop after a women has had her first child, the reason for this is not known but hormonal changes are suspected. It is also important to note that Rheumatoid Arthritis is one of those autoimmune conditions that can relate to other diseases (known as co-morbidity) and this includes Diabetes Type 1. There are also other complications from the condition including Sjorgren’s syndrome, depression and lung problems. People with RA have a two to four times higher risk of developing non-hodgkins lymphoma than those without. Other blood cancers, such as leukaemia and other forms of lymphoma, as well as lung cancer and melanoma, are also at a higher risk of occurring in those with RA. Not only is the disease itself a culprit, but some associated medications may be involved.

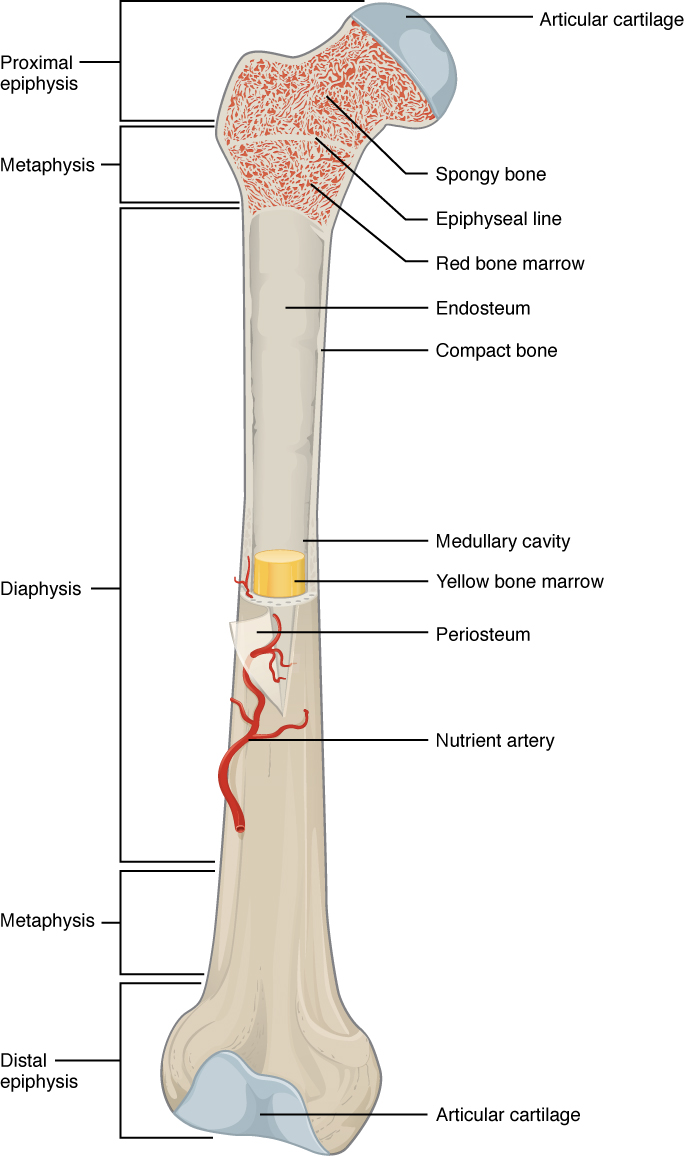

A review of the anatomy of bones and joints – to better understand Rheumatoid Arthritis

Bones have many layers to them. The outer layer, the periosteum, contains many pain receptors. As a result, this outer layer is highly sensitive to pain when damaged, and pain can therefore be present whether a person is moving or not. Someone experiencing a RA flare up will have little respite from pain, as rest doesn’t necessarily help. This is different to the experience of muscle pain.

The joint capsule consists of two layers, an outer fibrous capsule, and an inner layer called the synovial membrane. The synovial membrane is a thin, vascular lining that covers the inner surfaces of the joint capsule and intra-articular ligaments and tendons. For those particularly interested in reading more, this article is a highly detailed explanation of the knee joint capsule and the effects of RA.

The image below is a good visual representation of the differences between a normal joint and joints with Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis. As you can see in RA, the bone is eroding not at the end surfaces, but more at the growth plate line. The synovial lining essentially creates the fluid that helps the joints to slide on each other – it is like the oil that is used in machines to stop friction. When this fluid is reduced, friction can damage the bones from the outside of the bone inwards, due to constant wear and tear.

What is a ‘flare’?

RA is intermittent and whilst a person may have the condition, at any given time they may not be experiencing pain or deterioration. When symptoms return, it is known as a ‘flare’, and this is when pain occurs and deterioration progresses. During a flare, there can be redness and heat in the joints affected.

Why does a flare occur? We don’t really know, but fatigue can trigger a flare. Accordingly, fatigue management is important when working with a person with Rheumatoid Arthritis, and this will be discussed subsequently in this article.

Is it like Osteoarthritis?

Unlike Osteoarthritis, which is caused by wear and tear of the joint, Rheumatoid Arthritis is an autoimmune disorder. Around 80% of those affected have a Rheumatoid factor in their blood which is thought to cause the destruction of the joints.

How is Rheumatoid Arthritis diagnosed?

A person experiencing pain in the joints may end up visiting their Physiotherapist or other manual therapist. If the therapist suspects RA they should refer the person to their doctor. The General Practitioner will generally make enquiries and then refer a person to have:

// A blood tests measuring for inflammatory markers and the rheumatoid factor.

// X-rays are helpful to understand the amount of joint damage that has occurred.

If a person shows positive for RA they should then be referred to a Rheumatologists for assessment and treatment. There is a great deal of evidence that indicates that the most amount of damage done to bone occurs within the first two years of the disease. It is for that reason that early detection and interventions are essential.

What we have learnt from this is that diagnosing RA can take time, and many different appointments. By the time that a person is coming to see a movement teacher for a diagnosis they probably have seen many people and are in need of empathetic and appropriate movement of their body.

Rheumatoid Arthritis, Fatigue and Pain

Other symptoms of RA include fever and fatigue – important factors to remember when working with clients. The fatigue experienced with RA is not the sort of tiredness that can be fixed with a sleep in and a few days of relaxing. With this type of fatigue, a person does not feel rejuvenated by sleep, and they can feel very demotivated. However, research has shown that physical activity is important for managing fatigue. Furthermore, inactivity weakens the muscles that support their joints, leaving them susceptible to accelerated deterioration (Di Giuseppe et al., 2015). Not overdoing things and ‘pacing’ is essential when working with someone affected by RA.

Clients may describe fatigue as decreased muscle performance or an inability to perform a certain activity/task. Unhealthy lifestyles, toxic medications, and disruptive sleep patterns are described as potential sources of fatigue (Torres-Harding & Jason, 2005), whilst pain is described as an unpleasant emotional or sensory experience caused by potential/actual tissue damage (Merskey & Bogduk, 1994).

Pacing is a technique that can help reduce fatigue symptoms. The term ‘pacing’ is a strategy where the client is educated on how to maintain a balance between their daily activities and resting periods (Group, 2002).

Strategies for pacing in working with clients include:

// Using a pain scale, where a client identifies the level of pain between one and 10 that is experienced in doing an activity. The person should be identifying the perceived pain around a 4 level but no higher. Here is an example of a commonly used pain scale .

// Managing class sessions to shorter periods, particularly when a person first starts working with you or is experiencing a flare. In other words, rather than starting with a one-hour session, someone affected by RA may start with a 30-minute session or in some cases a 15-minute session. Over the years with some clients, we have started them with 3 sessions a week at 15 minutes each, and then over time progressed that to 30-minute sessions, 45-minute sessions, and then eventually one hour sessions.

// Remember if pain lasts for more than 2 hours then it is likely that joint damage is occurring

// Ensure that the session includes breathing exercises and other exercises that will help modulate the parasympathetic system. Remember there is a link between the immune system and the parasympathetic system. It is also important to incorporate breath and diaphragm conditioning work, as lung disorders are a common complication for people with RA.

// Make sure you have lots of props to help grade and modify exercises, so the person does not fatigue themselves. My favourite props apart from Pilates and gyrotonic equipment include towels, yoga blocks and Makarlu Lotus.

Medications and treatment

There is no cure for RA. Treatment of the condition includes:

// Medication

// Osteopathy

// Acupuncture and Massage

// Occupational Therapy

// Hydrotherapy

// Exercises such as Pilates

Medications

The goal of RA treatment is to avoid and reduce the likelihood of irreversible joint damage.

A common medication for RA is Methotrexate and other immune suppressant medications. This means that the person might be more susceptible to colds, flus and other infections. If you or any clients have a sniffle or in any way unwell, then you need to be careful to protect your client with RA by changing the appointments around or taking other measures to minimise their risk of infection.

The following is a video prepared by the Arthritis Australia about Methotrexate and Rheumatoid Arthritis. It is one hour long and is designed to inform medical practitioners, so make sure you have the time to listen to it if you are interested. It gives an insight into the process and considerations for diagnosis. There is a particularly important information around 6 minutes into the video about the importance of early diagnosis and intervention, as most damage to joints occurs within the first two years of the disease.

Biologics have been increasingly used for Rheumatoid Arthritis with mixed success. There are some risk factors that people need to be aware of when taking these medications. Biologics work by targeting different pathways of inflammation that play a role in the development of RA. However, biologics like methatrexate suppress your immune system, which can sometimes cause collateral damage, according to the American College of Rheumatology.

Some potentially serious side effects that might be related to biologic therapy include:

// Infection

// Reactivation of TB or another dormant infection, such as hepatitis B or C

// Cancer, such as lymphoma or skin cancer

// Neurological diseases including peripheral neuropathy

// Autoimmune reactions, such as lupus or vasculitis

Accordingly, when working with people with RA and taking these immune suppressing medications you should be particularly careful of:

// Bacterial infections – make sure you are using high grade disinfectants on cleaning equipment and the studio space

// Make sure people are not coming to work or into the studio with coughs and colds that can spread infections

// Keep an eye on client’s skin for heat, rashes and swelling. Small cuts can lead to conditions such as cellulitis

// Make sure you are not wearing long finger nails or jewellery that could accidentally nick or cut your clients, which could lead to infections

// Take care with scents in the studio as their sense of smell could be affected by the medications

Exercise considerations

To prevent inactivity from becoming entrenched, restoring motivation and overcoming fear of movement is very important in this condition. Inactivity and poor postural awareness can lead to structural changes to the joints , which will severely limit overall function. Accordingly, it is important that each class has a focus on space and alignment of all joints as well as strength.

Fatigue is a common side effect both of the disease as well as the medications that are taken to treat the disease. Fatigue management strategies such as exercising in the morning (or when the person affected has the most energy), taking breaks, and monitoring fatigue are important. It is also important to be careful of swelling and conditions like baker’s cysts and lymphoedema.

Joints will be very painful and the pain may be exacerbated with movement. Knowing that that there will be some discomfort with exercise is important, but you need to work within a pain tolerance for that person. Remember to refer to a pain scale and keep that person’s pain no higher than a 4 out of 10.

Joint protection includes the principle of pacing, mentioned earlier in this article. This principle includes:

// Little and often

// Take regular breaks

// Change position

// Stretch

// Mix heavy and light activities

// Don’t start activities that can’t be stopped

// Rest joints / relax body

Consideration 1: Protect joints

By changing the way in which a task is done or by using assistive devices (to modify how the task is done).

1. Avoid movement/positions in direction of deformities

2. Avoid positions that put pressure or stress on joints

3. Avoid sustained tension on muscles around affected joints (e.g. tight pinching/gripping)

4. Avoid static positions i.e. change positions frequently

5. Use the largest/most stable joint for the task e.g. this means instead of using fingers, use the wrist; instead of using the wrist, use the elbow; instead of using the elbow, use the shoulder etc.

6. Use assistive devices to reduce stress on joints

Make sure you use strategies that minimise load on specific joints and use things that can help support the joints from poor alignment. Ideas include lots of towels, balls, etc.

Isolated activation of gluteus muscles in side lie with lots of towels to support joints in optimal alignment.

Having the hands supported with a gentle curve – like on the timber base of Makarlu Lotus, or with the Baby Arc – can distribute force on the joints when in positions such as four point kneeling. I also use the Makarlu timber base to help with joint protection in the feet and ankles. Remember that ligamentous laxity is a common problem for people with RA and you need to be careful to build joint strength. I like to use things like the Balanced Body sling when working with people to support and focus on intrinsic muscle activation. Avoid movements in the directions of the deformities.

Consideration 2: Hand strength and grip ideas

As RA often affects the wrist or finger joints it can be difficult for a person to grip or use equipment. If the person has splints or protective devices for their hands it can be helpful to have them keep these on during class. It is important to try and work on some grip strength and to have the person keep their elbows and shoulders working. Here are some simple ideas to help with grip strength whilst doing shoulder or upper body work.

In this video I am using the velcro cuffs. I have recently found a particularly soft fleece version of the cuffs, and a little but longer and therefore more helpful one for different angles from a place called Elements by Momentum World. I really like them more than the ones I was using in this video. For the record I am NOT receiving any payment or gifts from this Momentum World, I just like their product for these client groups.

It is important to try and keep the intrinsic muscles as strong as possible, but be careful not to overload the joint. RA can create ligamentous laxity, and there is also fatigue that needs to be considered.

Idea : Hand or feet strengthening using a towel or Makarlu Lotus

Hand doming on the towel encourages intrinsic hand muscle use. However direct load on the wrist joint can be problematic for people. In that situation I put their hands onto the timber base of the Makarlu domes and use that as a means of encouraging intrinsic hand activation.

Similar concepts apply for the feet with the use of the towel or Makarlu timber domes in order to activate intrinsic muscle strength.

Use the towel under foot to encourage the person to strengthen the intrinsic muscles of their feet. You will often see people cheating by scrunching up their toes. To avoid this I put a pencil underneath their toes. I find the Makarlu timber dome is the easiest way to introduce this exercise and to help people activate the correct muscles.

In this exercise we are alternating the feet to activate the intrinsic muscles. We are also encouraging articulation of the foot off the Makarlu Dome.

In this exercise we are using the Makarlu domes under both feet. This is to encourage the strengthening of the intrinsic muscle of the feet, and to facilitate improved proprioception.

Some other ideas I like to use to help build strength in the hands are things like marble putty, in which you put a marble into putty and the person has to use one hand in order to get the marble out.

Put marbles into putty and have the person use only the fingers of the hand holding the putty to work the marble out.

Another idea is to incorporate graded weight training. Remembering though that a client can have a lot of pain in their joints and gripping traditional weights or something too heavy for them can cause real tissue damage. It is important to make graded changes to the weight training of clients that is respectful of the client’s tolerance for pain. In this video the first 2 minutes is about how to use the Makarlu, just skip to about 2.09 minutes into the video for ideas about hands and wrists.

Consideration 3: Traction of the joints, and use of springs and resistance to help with correct muscle activation and joint alignment.

When you use the Pilates apparatus, the springs and load can be varied so that the person is able to strengthen the muscle without loading the joints. It is important to keep muscles strong and the person active to protect a joint.

I like the use of the CoreAlign in this twisted angel example as a way of helping build strength without the person having to compress in the joints of the back and knee.

In this scenario we are using the traction of the arms to help maintain shoulder range without having to use finger grip.

The sling can be a great way to traction the joint when working in exercises like pike. I like this exercise as it can help decompress the lumbosacral region which can often be affected by RA.

Consideration 4: Progressive stretch and release

Progressive stretching and release of muscles around the joint whilst still working the muscles can also be a great way to protect the joint and train it proprioceptively. Remember that whilst the hands and feet may be affected, joints like the shoulder or hip can be working overtime in order to compensate. Accordingly, it is important to make sure that you keep muscles in these adjacent areas released and strong.

Avoid high impact on the affected joints, while unaffected joints might be able to tolerate higher loaded work. If a person is doing high intensity work, it is important to consider is that raised cortisol levels and the stress response can aggravate the inflammatory process.

Consideration 5: Balance and falls

Remember that the balance system consists of the proprioception, visual and vestibular systems. Rheumatoid Arthritis has particular affects on the proprioceptive system, through its destruction of joints and its potential impact on the eyes. Accordingly, working on balance is essential to prevent falls and breakages. Remember, people with this disease will often have medications that affect and increase the likelihood of the development of osteoporosis. To help these people make sure you work on balance and reaction times.

Ideas that I like for helping with balance include things like working on the CoreAlign, Makarlu slider and on the reformer. We consider balance and vestibular issues so important that there is a whole chapter in our Autoimmune and Cancer course manual, which you receive when doing that course.

We have already written some articles on exercises for various conditions and I will refer you to:

// Hand exercises for arthritis

// Peripheral neuropathy and exercises

// Lymphoedema and exercises

Rheumatoid Arthritis and hand strength is a topic we cover in our online Anatomy Dimensions courses, in particular the Upper Limbs courses and the Autoimmune and Cancer courses. If you are interested in participating in a course or wanting to see one of our practitioners for help, please feel free to email us at info@bodyorganics.com.au.

To buy Makarlu Lotus

References

Astin, J.A., et al., Psychological interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, in Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2002. p. 291- 302.

Di Giuseppe, D., Bottai, M., Askling, J., & Wolk, A. (2015). Physical activity and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women: a population-based prospective study. Arthritis research & therapy, 17(1), 40.

Fujii K, Tsuji M, Tajima M (1999) Rheumatoid arthritis: a synovial disease? Ann Rheum Dis 58(12):727–730

Group, c. m. W. (2002). A report of the CFS/ME Working Group: report to the chief medical officer of an independent working group: Department of Health.

Hammond, A. and K. Freeman, The long-term outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of an educational-behavioural joint protection programme for people with rheumatoid arthritis, in Clinical Rehabilitation 2004. p. 520-528.

Masiero, S., Boniolo, A., Wassermann, L., Machiedo, H., Volante, D., & Punzi, L. (2007). Effects of an educational–behavioral joint protection program on people with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rheumatology, 26(12), 2043-2050.

Merskey, H., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Classification of chronic pain, IASP Task Force on Taxonomy. Seattle, WA: International Association for the Study of Pain Press (Also available online at www. iasp-painorg).

Mohanty,B., Padhan P.,Singh,P. (2018) Comparing the effect of Proprioceptive retraining technique against home exercise programme on hand functions in patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Inidian Journal of Physiotehrapy and Occupational Therapy, July- September 2018, vol 12.No.3

Nijs, J., Van Eupen, I., Vandecauter, J., Augustinus, E., Bleyen, G., Moorkens, G., & Meeus, M. (2009). Can pacing self-management alter physical behaviour and symptom severity in chronic fatigue syndrome?: A case series. Journal of rehabilitation research and development, 46(7), 985-969.

Nordenskioöld, U. (1996). Daily activities in women with rheumatoid arthritis: Aspects of patient education, assistive devices and methods for disability and impairment assessment. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 3(2), 91. doi:10.3109/11038129609106689

Ospelt C, Gay S (2008) The role of resident synovial cells in destructive arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 22(2):239–252

Shepherd, C. (2001). Pacing and exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. Physiotherapy, 87(8), 395-396.

Thyberg, I., Hass, U. A., Nordenskiöld, U., & Skogh, T. (2004). Survey of the use and effect of assistive devices in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: A two‐year followup of women and men. Arthritis Care & Research, 51(3), 413-421.

Suomi, R. and D. Collier, Effects of arthritis exercise programs on functional fitness and perceived activities of daily living measures in older adults with arthritis, in Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2003. p. 1589-94.

Torres-Harding, S., & Jason, L. A. (2005). What is fatigue? History and epidemiology. Fatigue as a window to the brain, 1, 3-17.

Townsend, E., Polatajko, H., Craik, J., & Davis, J. (2007). Canadian model of client-centred enablement. EA Townsend and HJ Polatajko, Enabling occupation II: Advancing occupational therapy vision for health, well-being and justice through occupation, 87-151.

White, P., Goldsmith, K., Johnson, A., Potts, L., Walwyn, R., Decesare, J., . . . Pace Trial Management, G. (2011). Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. 377(9768), 823-836. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60096-2

0

0